AI coding platform's flaws allow BBC reporter to be hacked

Good Luck, Have Fun, Don't Die rails against AI in style

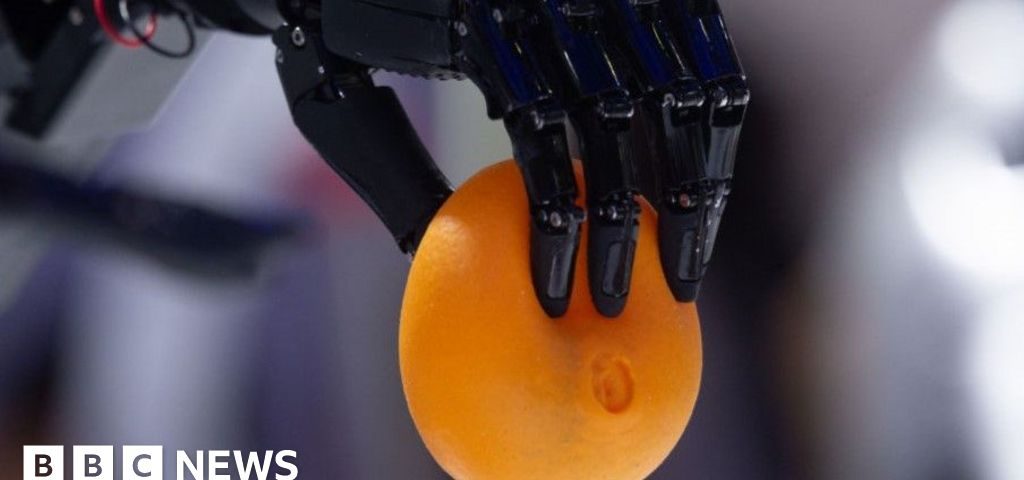

Get a grip: Robotics firms struggle to develop hands

Kacper Rozanski operates Shadow Robot hands

Made with wood, springs and rubber bands, Rich Walker remembers fondly the first robotic hand built by Shadow Robot in the late 1990s.

"A lot of it was done with just stuff that we had," says Walker, now a company director.

I'm in Shadow Robot's north London headquarters, looking at their latest robotic hands.

Cylindrical "forearms" house small electric motors, known as actuators, which pull on metal tendons that move the fingers with precision.

To use the robotic hands, sensors are strapped to my fingers and I'm given a few simple instructions.

As a beginner, I expected the arms and hands to flail around, knocking the blocks and cups around the room.

But the movements are smooth and precise, and straight away I was manipulating the blocks and cups.

Around 200 of these hands are in use, mostly by researchers at universities and tech firms.

"This is essentially a development kit for dexterity. You get this hardware, you explore what can be done in terms of dexterity, then that helps you work out what you want to build if you're going to build a bigger system, or a bigger project, or deploy something," explains Walker.

Rich Walker has been developing robot hands for 30 years

Such development work needs to be done if robots are to navigate the human world, where almost all tools and devices are designed for the human hand.

"I think the hand is the hardest, most complex part of any humanoid robot," says Bren Pierce, the founder of robotics start-up, Kinisi, based in Bristol.

Ten of its KR1 robots are undergoing trials in commercial settings. They can be fitted with different grippers, depending on what the robot has to do. Strong "gorilla" pincers are used for picking up heavier boxes or, for more delicate items, a suction device can be used.

But like most in the industry, Pierce would like to offer one hand, flexible enough to do everything.

"Everyone has been dreaming for 40 years of one robot hand to rule the world. A lot of people think it could be the humanoid hand," says Pierce.

His company has built a three-fingered hand which he says is "pretty good".

"But now it's a case of how do you make it robust, how do you make it at scale, and how do you actually make it at a reasonable price?"

Kinisi's prototype hand cost around £4,000 (s KR1 robot, fitted with pincers and suction cups

The challenge of developing a robust, dexterous and affordable hand was underlined by Tesla-boss Elon Musk, when he spoke at the All-In Summit in Los Angeles in September of last year.

He identified creating a hand as one of the three most difficult problems facing makers of humanoid robotics. The other two were creating an artificial intelligence that allowed the robot to comprehend the world, and making robots in large numbers.

So, a lot of attention will be paid to the latest version of Tesla's humanoid robot, Optimus, when it is launched this year.

Musk promised it will have "the manual dexterity of a human, meaning a very complex hand".

"Rubbish," says Nathan Lepora, Professor of Robotics and AI at Bristol University. He has spent his career working on robot hands and says human level dexterity is still some way off.

"It won't happen in two years, but we might be talking about 10 years for this to happen, and that's still a short period of time," he says.

Lepora is currently working on a robotics project under the UK government's Aria research and development scheme.

Like the Shadow Robot hand, Lepora works on hands with "tendons" that move the fingers.

"Longer-term I think that tendon-driven hands using more sophisticated mechanisms will result in more affordable and capable hands," he says.

However, he has been impressed with the progress made by Chinese firms who, instead of tendons, are using motors in the fingers and hands to drive movement.

"In China, the people who make motors are getting together with the people who make hand hardware and basically creating bespoke motors that can fit within joints and fingers. It's probably going to work as an effective hand," he says.

Wuji Technology, based in Shanghai, is one of those firms.

Each finger in its latest hand has four independently controlled joints, which allows intricate movements.

Wuji co-founder, Yunzhe Pan, says the hand is durable as well. "And we will make it more durable in the next generation," he adds.

At the moment each hand sells for we will be making it more affordable in the future," says Pan.

The Wuji hand has piezoelectric sensors, which convert pressure into an electrical charge, giving it a sense of touch.

Giving robots a durable sense of touch will be a breakthrough for humanoid robots.

But it's another area that needs a lot of work, says Pierce.

"When you go around research labs, or you talk to start-ups, they have really good sensors, and then you ask them how long they work. They say 'six months'. That's great for R&D… but in industry, I want this robot to work for 10 years," he says.

There is reason to be optimistic though.

Historically, tactile sensing always seemed like a technology that was 10 years away, Lepora says. But he thinks the billions of dollars being invested in humanoid robots is making a difference.

"Things are changing," he says.

More Technology of Business

AI ready: The advantages of being a young entrepreneur

Can India be a player in the computer chip industry?

The 'magical' blue flower changing farmers' fortunes in India

Technology of BusinessInternational businessTechnology

Original aticle here: BBC